This is Part II of my “From Disruption to Direction” series. In Part I, I reflected on my journey with Integra and the broader transformations reshaping education publishing. In this follow-up, I turn my attention to a question that dominates nearly every strategic conversation I have with publishers: How is artificial intelligence actually being adopted across our ecosystem?

The answer, I’ve learned, is far from simple.

AI is not a single event or uniform phenomenon. It’s a distributed force—interpreted, prioritized, and operationalized differently by each stakeholder group. What excites a technology vendor may concern an educator. What policy makers view as essential guardrails may feel like constraints to innovators. What works brilliantly in higher education may fail completely in K-12 contexts.

My aim in this article is to map those perspectives with clarity and nuance—to show where they overlap, where they diverge, and most importantly, where they create opportunities or tensions that publishers must navigate. I’ll examine how three critical communities are engaging with AI:

- Industry service providers and technology vendors who build and sell AI-enabled solutions

- Educators and learning practitioners who use these tools with real students in real classrooms

- Policy makers and regulators who set the frameworks within which innovation must operate

Understanding these perspectives isn’t academic—it’s essential strategy. Publishers operate at the intersection of all three constituencies. Success requires fluency in each worldview and the ability to translate between them.

Let’s explore what each group sees when they look at AI in education publishing.

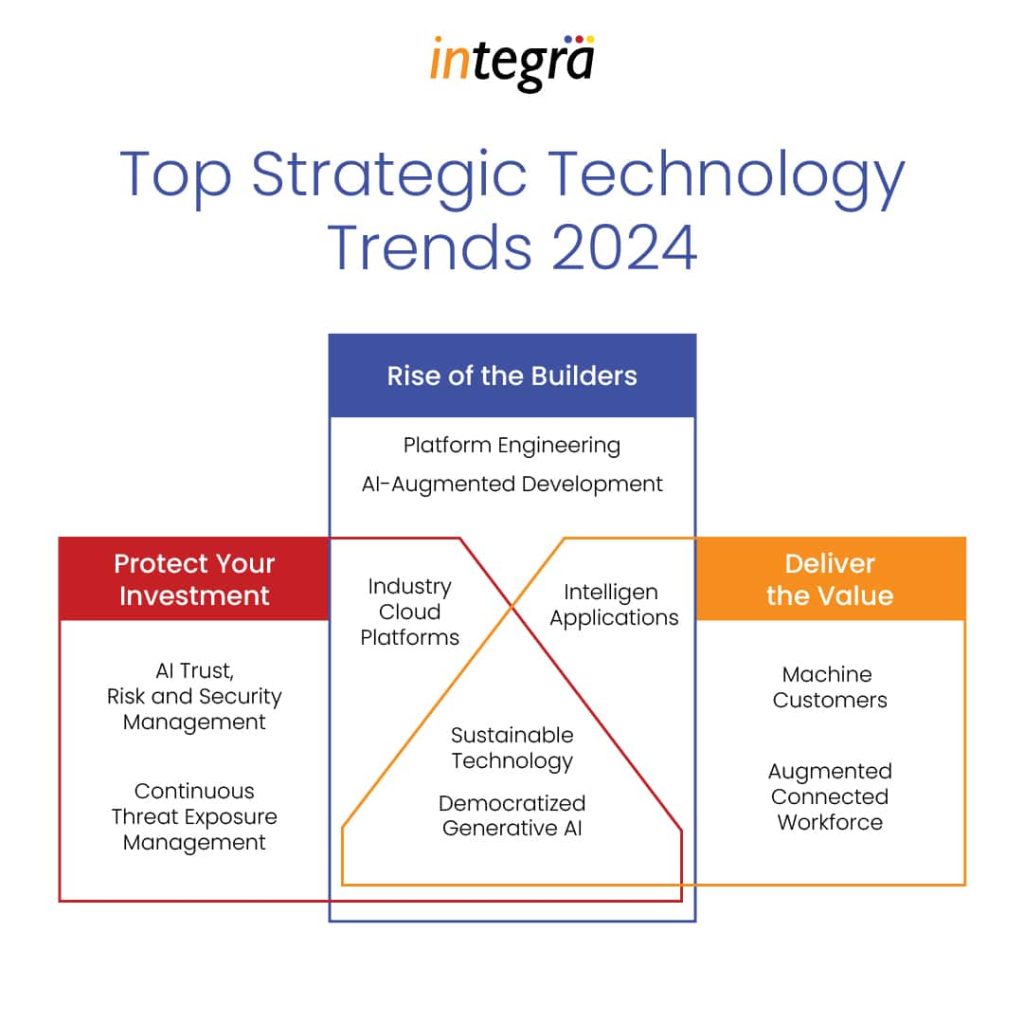

1. Industry Service Providers and Technology Vendors

For vendors and service providers like Integra, the question driving AI development is fundamentally pragmatic: How can AI create measurable value for publishers while protecting the standards, quality, and reputation that define their brands?

How They See AI

AI as a capability enabler

Vendors are systematically embedding machine learning across every stage of the educational content value chain. Consider the breadth of application:

- Metadata enrichment and taxonomy management that automatically tags and categorizes content to improve discoverability

- Automated quality control that catches errors, inconsistencies, and accessibility issues before publication

- Intelligent reviewer and editor matching that pairs manuscripts with the most qualified experts

- Production automation that accelerates layout, formatting, and asset processing

- Neural machine translation that makes content available across languages faster and more affordably

- Adaptive learning engines that personalize content delivery based on learner performance and preferences

- Predictive analytics that help publishers understand adoption patterns, usage trends, and content effectiveness

These aren’t experimental features anymore—they’re moving rapidly from pilots into core platform capabilities because they demonstrably reduce friction, unlock scale, and improve outcomes.

AI as a competitive differentiator

In a crowded market where vendor offerings increasingly converge on price and features, intelligent automation and sophisticated analytics have emerged as decisive competitive advantages.

Publishers evaluating partners want to see evidence of AI maturity: not just that you have AI capabilities, but that you’ve operationalized them successfully. They want case studies showing time saved, quality improved, costs reduced, and learner outcomes enhanced. Vendors who can demonstrate this track record win long-term contracts; those who can’t face commoditization pressure.

AI as a product design constraint

Here’s the challenge that separates serious vendors from opportunistic ones: AI systems for education publishing must be explainable, auditable, and integrable with existing workflows.

It’s not enough to build a model that works in isolation. It must work within publishers’ complex technology ecosystems—often involving decades-old systems, bespoke workflows, and integrations with multiple platforms. It must provide transparency about how decisions are made. And it must include human oversight points where editorial judgment can intervene.

This constraint actually improves design. It forces vendors to build systems that serve human decision-makers rather than attempting to replace them.

Key Concerns

Integration complexity

The education publishing landscape is extraordinarily heterogeneous. A single publisher might operate different content management systems for different imprints, use various learning management system (LMS) integrations, and maintain custom workflows built over years to match their specific editorial processes.

Vendors must offer modular, interoperable solutions with well-documented APIs that reduce disruption during deployment. “Rip and replace” strategies rarely succeed. Successful implementations involve careful phasing, parallel operation periods, and extensive change management.

Explainability and trust

When an AI system recommends rejecting a manuscript, matching a particular reviewer, or adapting content presentation for a learner, publishers need to understand why. Black-box algorithms are unacceptable, especially for editorial or assessment decisions that directly impact educational outcomes.

This demand for explainability is intensifying. Clients want documentation of training data sources, model architectures, decision logic, and confidence intervals. They want the ability to audit decisions and override when necessary. They want to explain to their stakeholders—authors, educators, institutions—how these systems work.

Data and intellectual property governance

Training AI models on publishers’ proprietary content raises complex questions. Who owns the outputs? Can the model be used for other clients? What happens to sensitive learner data? How do we ensure compliance with privacy regulations across multiple jurisdictions?

These aren’t merely legal questions—they’re trust questions. Vendors who provide clear, publisher-friendly answers to these concerns build lasting partnerships. Those who remain vague or evasive lose opportunities, regardless of technical capabilities.

The Directional Implication

Service providers who will lead in this space are those who deliver AI as a governed capability: measurable, auditable, and supported by robust human-in-the-loop controls.

For publishers, this means fundamentally changing your vendor evaluation criteria. Don’t just ask “Can you do AI?” Ask instead:

- Can you show me documented outcomes from existing implementations?

- What governance frameworks do you use?

- How do you ensure transparency and auditability?

- What training and change management support do you provide?

- How do you handle data privacy and IP rights?

Choose partners who can demonstrate answers, not just promise capabilities.

2. Educators and Learning Practitioners

Educators represent the most human-centered perspective in this ecosystem. Their lens is inherently pedagogical: What genuinely helps learners learn better, more equitably, and more deeply?

This community includes K-12 teachers, higher education faculty, instructional designers, curriculum specialists, assessment experts, and learning experience designers. Their concerns are grounded in daily classroom realities rather than technological possibilities.

How They See AI

AI as a time liberator

Ask educators what they need most, and time consistently tops the list. Time for meaningful feedback. Time for struggling students. Time for curriculum innovation. Time for their own professional development.

AI offers genuine promise here. Automating routine tasks—marking objective assessments, generating practice quizzes, creating multiple versions of assignments to prevent plagiarism, producing differentiated learning pathways—can return substantial time to educators.

The key word is routine. Educators embrace automation for tasks that don’t require pedagogical judgment. They remain skeptical about AI handling tasks that do—and rightly so.

AI as a personalization engine

The promise of adaptive learning has captivated education technology for years: systems that tailor content difficulty, pacing, modality, and support to individual learner needs in real time.

When it works well, adaptive technology can be transformative—especially for learners at the extremes of the ability spectrum who are often underserved by one-size-fits-all instruction. Advanced students progress faster without being held back. Struggling students receive additional support and alternative explanations without feeling singled out.

But educators have also witnessed adaptive systems that fail: creating fragmented learning experiences, making inappropriate inferences from limited data, or optimizing for superficial metrics (like completion rates) rather than deep learning.

Their enthusiasm for AI personalization is real but conditional. They want systems that genuinely understand learning progressions, respect pedagogical principles, and keep teachers informed and empowered.

AI as an accessibility tool

For many educators, this is where AI’s promise feels most concrete and immediate. Automated transcription makes video content accessible to deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Alt-text generation helps make visual content available to blind students. Text simplification and language translation support English language learners and students with reading difficulties.

These accessibility features don’t just serve students with disabilities—they benefit anyone consuming content in challenging circumstances: commuting students watching videos without sound, international students processing technical material in a second language, or learners with temporary impairments.

Educators see AI accessibility tools as extensions of their commitment to inclusive pedagogy. They’re eager adopters—provided the tools work reliably and integrate smoothly into existing workflows.

Key Concerns

Pedagogical integrity

This is the deepest concern I hear from educators: that over-reliance on AI may erode the very processes that create meaningful learning.

They worry about students using AI to bypass cognitive work—having ChatGPT write essays without engaging with the thinking process that essay writing develops. They worry about adaptive systems that optimize for correct answers while shortcutting the productive struggle that builds understanding. They worry about assessment becoming a game of detecting AI use rather than measuring genuine learning.

More fundamentally, they worry about losing the human dialogue that lies at the heart of education—the Socratic questioning, the responsive feedback, the relationship-building that makes teaching transformative rather than merely transactional.

These concerns aren’t technophobia. They’re grounded in deep understanding of how learning actually works. Any AI strategy that dismisses these worries will fail in the classroom.

Equity of access

Educational inequality haunts every conversation about technology. The worry is straightforward: if AI-enabled learning platforms, AI-assisted tutoring, and AI-powered personalization are expensive, they’ll concentrate in well-resourced schools and districts, while under-resourced institutions continue with traditional methods.

This isn’t hypothetical—we’ve seen this pattern with every previous educational technology wave. The result is a growing gap between technological haves and have-nots that correlates strongly with existing socioeconomic inequalities.

Educators in under-resourced settings are particularly attuned to this dynamic. They see AI announcements and wonder: “Will this actually reach my students, or will it widen the gap?”

Publishers and vendors who ignore this concern will find themselves facing both ethical criticism and market limitations.

Teacher preparedness and professional development

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: most educators lack formal training in AI literacy and the instructional design required for AI-enhanced learning environments.

How do you design assignments when students have access to AI writing tools? How do you interpret data from adaptive learning systems? How do you explain AI-generated feedback to students and parents? How do you integrate AI tools while maintaining your pedagogical approach?

These questions require new skills, new frameworks, and new professional learning communities. Yet professional development resources are often the first budget item cut during financial constraints.

The result is teachers encountering AI tools without adequate preparation—leading to underuse, misuse, or abandonment of potentially valuable capabilities.

The Directional Implication

Successful AI adoption requires systems designed with teachers, not just for them.

This means:

- Co-design processes that involve educators from the earliest stages of product development, not just as beta testers

- Sustained professional development that goes beyond one-time training to ongoing support and community-building

- Pedagogical transparency that explains how AI tools support specific learning objectives and teaching practices

- Teacher agency preserved through systems that inform and empower rather than constrain or replace professional judgment

- Gradual implementation that allows educators to build confidence and competence progressively

Publishers and platform teams who commit to these principles build lasting adoption. Those who treat educators as passive recipients of technology—no matter how sophisticated—will face resistance and failure.

3. Policy Makers and Regulators

Policy makers occupy a unique position in the AI ecosystem. Their role is to translate societal values into frameworks—rules, incentives, standards, and funding mechanisms—that maximize public benefit while minimizing harm as AI scales across education and publishing.

This community includes education ministers, regulatory agency officials, legislative staff, public funding bodies, accreditation organizations, and standards-setting institutions. They operate on different timelines and with different constraints than vendors or educators.

How They See AI

AI as an opportunity for system-level transformation

Policy makers see AI’s potential to address long-standing challenges in education at scale:

- Expanding access to quality learning experiences beyond geographic and economic constraints

- Accelerating innovation in curricula, assessment methods, and credentialing

- Supporting lifelong learning through personalized skill development and microcredentialing

- Improving educator effectiveness by reducing administrative burden and providing better learner insights

- Enhancing educational research through better data collection and analysis

These opportunities are compelling, particularly for systems struggling with teacher shortages, budget constraints, and demands for accountability.

AI as a risk requiring regulation

Simultaneously, policy makers recognize serious risks that require active governance:

- Algorithmic bias that perpetuates or amplifies existing inequalities in student outcomes

- Privacy violations as student data flows into commercial systems with inadequate protection

- Opacity and accountability gaps when AI systems make consequential decisions without transparency

- Commercial capture where profit motives override educational public good

- De-skilling risks if excessive automation erodes professional judgment and expertise

- Market concentration as dominant platforms create lock-in effects and reduce competition

The challenge is designing policy frameworks that encourage beneficial innovation while preventing these harms—without stifling development through overly restrictive regulation.

Key Concerns

Accountability and liability

When an AI system makes a wrong recommendation with serious consequences, who bears responsibility? If an adaptive assessment incorrectly places a student in a remedial track, affecting their educational trajectory—is the publisher liable? The platform provider? The institution that deployed it? The procurement officer who chose it?

These questions become even more complex when systems involve multiple vendors, open-source components, and automated decision chains where no single human made the final call.

Policy makers are working to establish clear accountability frameworks, but the technology is evolving faster than regulation can typically move. This creates uncertainty that both enables and constrains innovation.

Privacy and data protection

Student data deserves the highest level of protection. It’s sensitive, it involves minors, and it can have long-term implications for individuals’ opportunities and life trajectories.

Yet AI systems are inherently data-hungry. They improve through exposure to large, diverse datasets. Training effective personalization engines requires detailed information about learning patterns, struggles, preferences, and performance.

Reconciling these tensions requires sophisticated technical approaches (like federated learning and differential privacy), clear legal frameworks (like GDPR and FERPA compliance), and robust oversight mechanisms.

Policy makers are particularly concerned about data being used beyond its original educational purpose—for example, being monetized for targeted advertising or sold to data brokers. They want strict limits on data retention, clear consent mechanisms, and strong enforcement of violations.

Equity and public funding

Public education systems operate under fundamental equity mandates: every child deserves access to quality education, regardless of family income or geographic location.

AI creates equity challenges on multiple levels:

- Access inequality: If AI tools are expensive, wealthy districts adopt them while poor districts can’t afford them

- Outcome inequality: If AI systems are trained primarily on data from affluent, majority-culture students, they may serve those students better while underperforming for others

- Infrastructure inequality: AI tools often require reliable high-speed internet and modern devices—resources not uniformly available

Policy makers must design funding formulas, procurement rules, and implementation mandates that prevent these inequalities from widening. This might include requirements for universal access, diverse training data, or subsidized deployment in under-resourced settings.

The Directional Implication

Policy makers want frameworks that enable responsible experimentation under clear standards: transparency, auditability, fairness, and privacy by design.

They want to encourage:

- Interoperability and open standards that prevent vendor lock-in

- Public interest uses of AI that prioritize educational outcomes over commercial returns

- Participatory governance involving educators, students, families, and communities in decision-making

- Evidence-based adoption with rigorous evaluation of effectiveness and equity impacts

They want to discourage:

- Closed proprietary systems that lock institutions into single vendors

- Data exploitation that monetizes student information beyond educational purposes

- Opaque algorithms that make consequential decisions without explanation

- Inequitable access that advantages already-privileged populations

For publishers, this means building policy engagement into your strategy from the start—not as an afterthought when regulations arrive, but as a proactive partnership in shaping responsible frameworks.

4. Synthesizing the Three Perspectives

When you place these viewpoints side by side, patterns emerge that should fundamentally shape strategy for publishers, vendors, and platform providers.

Let me highlight five critical convergences and tensions:

1. Alignment on Augmentation, Not Replacement

Here’s the good news: vendors, educators, and policy makers converge on the value of human-plus-machine models.

None of these constituencies wants AI to replace human judgment in high-stakes decisions. Vendors recognize that “AI replacing teachers” is both pedagogically unsound and politically untenable. Educators insist on maintaining professional agency. Policy makers mandate human accountability.

The practical work ahead is designing the interfaces where humans make final, accountable decisions—ensuring AI provides insight and recommendations while preserving professional judgment for editorial choices, assessment decisions, and pedagogical adaptations.

This isn’t a technical challenge alone—it’s a design philosophy that must permeate every product decision.

2. Trust Is the Currency

Explainability, audit trails, and human oversight aren’t optional features—they’re fundamental requirements for adoption.

Trust is earned through:

- Transparency about how systems work and what data they use

- Reproducible processes that produce consistent results under similar conditions

- Visible governance with clear policies and accountable decision-makers

- Track records of responsible deployment and responsive problem-solving

Publishers who invest in building this trust will differentiate themselves. Those who treat it as a compliance checkbox will struggle with adoption and retention.

3. Skills and Change Management Matter Most

Here’s an insight that surprised me early in my career but has been validated repeatedly: technology without workforce transformation yields limited returns.

The most sophisticated AI system produces minimal value if:

- Editors don’t understand how to use it effectively

- Teachers don’t trust it enough to incorporate it into practice

- Institutional leaders don’t know how to measure its impact

- Support teams can’t troubleshoot issues or explain features to users

Publishers must budget for training, role redesign, and organizational change management at least as much as for software licenses and implementation. The ratio I recommend: for every dollar spent on technology, allocate at least 50 cents to people development.

This isn’t overhead—it’s the investment that determines whether technology adoption succeeds or fails.

4. Equity Must Be a Design Requirement, Not an Afterthought

Building accessibility and fair access into product design and procurement processes will determine whether AI closes or widens opportunity gaps.

This requires concrete commitments:

- Universal design principles from the earliest stages of product development

- Diverse training data that represents the full spectrum of learners

- Transparent bias testing with published results and remediation plans

- Tiered pricing models that make tools available to under-resourced institutions

- Offline and low-bandwidth options for contexts with limited connectivity

- Regular equity audits examining differential outcomes across student populations

Equity isn’t a feature you add at the end—it’s a lens you apply throughout the entire development and deployment process.

5. Business Models Must Evolve Beyond Content Access

In K-12 and higher education publishing, value is shifting dramatically from content access to services that demonstrate learning impact, enhance discoverability, and ensure integrity.

Consider what institutions are willing to pay for:

- Learning analytics that help faculty identify struggling students early

- Accessibility features that expand reach to diverse learners

- Assessment tools that provide formative feedback and measure authentic skills

- Integrity services that detect plagiarism and verify learning

- Integration services that reduce technical friction

- Professional development that increases effective use

Publishers who can package these services—with AI as an enabling capability rather than the product itself—will sustain revenue in an increasingly open content ecosystem. Those clinging to access-control business models will face mounting pressure.

This shift requires reimagining not just products but entire value propositions, pricing structures, and go-to-market strategies.

5. Practical Steps for Publishers

If you’re responsible for strategy, product development, or partnerships at an education publishing house, here are focused actions to move from disruption to direction:

1. Define Measurable Outcomes First

Don’t start with “we need an AI strategy.” Start with “we need to solve these specific problems.”

Identify one or two clear use cases where AI can deliver measurable improvement in time, cost, or learner outcomes:

- Reducing editorial review time by X%

- Improving accessibility compliance from Y% to Z%

- Increasing learner engagement or completion rates by X points

- Accelerating time-to-market for new content by Y weeks

Build pilots around these use cases. Measure rigorously. Learn and iterate. Scale what works.

Specificity and measurement discipline separate successful AI initiatives from expensive experiments that yield little value.

2. Adopt a Human-in-the-Loop Model

Require human review gates for editorial decisions, integrity assessments, and high-stakes determinations that affect educational outcomes.

This means:

- AI can recommend, but humans decide on manuscript acceptance, reviewer selection, or content quality judgments

- AI can flag potential issues, but humans investigate and resolve questions about plagiarism, data integrity, or bias

- AI can suggest learning pathways, but educators validate and adjust based on pedagogical judgment and knowledge of individual students

Document these governance points clearly. Train staff on when and how to exercise oversight. Create audit trails showing human decisions, not just AI recommendations.

3. Select Partners on Governance, Not Just Capability

When evaluating AI vendors, shift your criteria from “what can they do” to “how do they do it responsibly.”

Ask for:

- Model documentation: What data was used for training? What are the model architectures? What are known limitations?

- Data provenance: Where did training data come from? How is IP protected? How is privacy ensured?

- Audit features: Can we see why specific decisions were made? Can we override when necessary?

- Governance frameworks: What policies govern AI use? How are they enforced? How are they updated?

- Track record: What published case studies demonstrate successful, responsible deployment?

Partners who can’t provide clear answers to these questions aren’t ready for high-stakes educational deployments, regardless of their technical capabilities.

4. Invest in People, Not Just Technology

Create comprehensive training roadmaps for:

- Editors and content developers to work effectively with AI tools in their workflows

- Learning designers to create AI-enhanced experiences that maintain pedagogical integrity

- Customer success teams to support institutional clients through adoption

- Sales teams to articulate value propositions that resonate with each stakeholder perspective

- Leadership teams to make strategic decisions about AI investments and partnerships

Include not just initial training but ongoing learning communities, refresher courses, and advanced skill development.

Budget adequately—remember the 50% rule mentioned earlier. If you spend $1 million on AI technology, allocate $500,000 to people development.

5. Embed Equity Metrics Throughout

Don’t wait until deployment to discover that your AI system works better for some populations than others. Build equity measurement into every stage:

- Design phase: Are diverse learners represented in personas and use cases?

- Development phase: Is training data representative of all populations who will use the system?

- Testing phase: Are you measuring differential performance across demographic groups?

- Deployment phase: Are you tracking access, adoption, and outcomes by student population?

- Ongoing operation: Are you conducting regular equity audits and publishing results?

Create dashboards that make equity metrics visible to decision-makers. Establish intervention protocols when disparities emerge. Make equity a standing agenda item in governance meetings.

6. Engage Policy Makers and Institutions Proactively

Don’t wait for regulation to find you—be proactive in shaping responsible frameworks.

This means:

- Participating in policy sandboxes and pilot programs that test AI in controlled settings

- Contributing to standards development processes for educational AI

- Publishing transparency reports about your AI systems and their performance

- Engaging with public procurement processes that reward openness and accountability

- Supporting research collaborations that rigorously evaluate AI effectiveness and equity

Position your organization as a responsible innovator rather than a reluctant compliance follower. This builds reputation, creates early-mover advantages, and shapes policy in ways aligned with your values.

6. Final Thoughts: Shaping the Future Together

AI will not be a single technology event that disrupts education and then settles into a new equilibrium. It will be a long, adaptive conversation between technology capability, pedagogical practice, and public interest.

The publishers who will lead this transformation share specific characteristics:

They build trusted systems that prioritize transparency, accountability, and human oversight over maximal automation.

They invest in people alongside technology, recognizing that organizational capability matters more than technical sophistication.

They commit to equitable outcomes through deliberate design, measurement, and remediation—not as corporate social responsibility theater but as core business strategy.

They engage all stakeholders as partners rather than treating vendors as suppliers, educators as users, and policy makers as obstacles.

They measure rigorously and adapt based on evidence rather than assumptions or hype.

Integra’s Commitment

At Integra, these principles shape our work every day. We design AI-enabled services that prioritize:

- Governance and accountability through transparent processes and human-in-the-loop controls

- Teacher and editor agency by building tools that inform and empower rather than constrain professional judgment

- Accessibility and inclusion as design requirements from the earliest stages, not afterthoughts

- Measurable impact on learning outcomes, operational efficiency, and quality assurance

We partner with publishers to pilot innovations in controlled settings, measure results rigorously, and scale solutions that deliver real learning and research impact.

A Call to Purposeful Direction

The second act of our industry’s transformation requires something more deliberate than reaction to disruption. It requires direction—chosen with purpose, grounded in evidence, and centered on the communities we serve.

This direction emerges not from any single stakeholder but from the synthesis of perspectives: vendors bringing technological capability, educators bringing pedagogical wisdom, policy makers bringing societal values, and publishers bringing it all together in service of learning.

The future we’re building isn’t predetermined by technology. It’s being actively shaped by the choices we make today—choices about what to build, how to deploy it, who to serve first, what to measure, and what values to embed.

Let’s make those choices wisely, together.

About the Author

Piyush Bhartiya is Senior Vice President, Key Account Management at Integra. He leads strategic partnerships with global education publishers across K-12 and higher education markets and brings more than 20 years of experience in digital content, learning design, and educational transformation. Piyush focuses on building solutions that combine pedagogical excellence, technological innovation, and accessibility—ensuring that scalable education becomes truly inclusive. He is passionate about helping publishers navigate complex transformations while staying true to their educational missions and values.

Connect with Piyush: LinkedIn | Email

Learn more about Integra’s education services: Visit our Services Page